Music is not a level playing field — it is a field of all levels

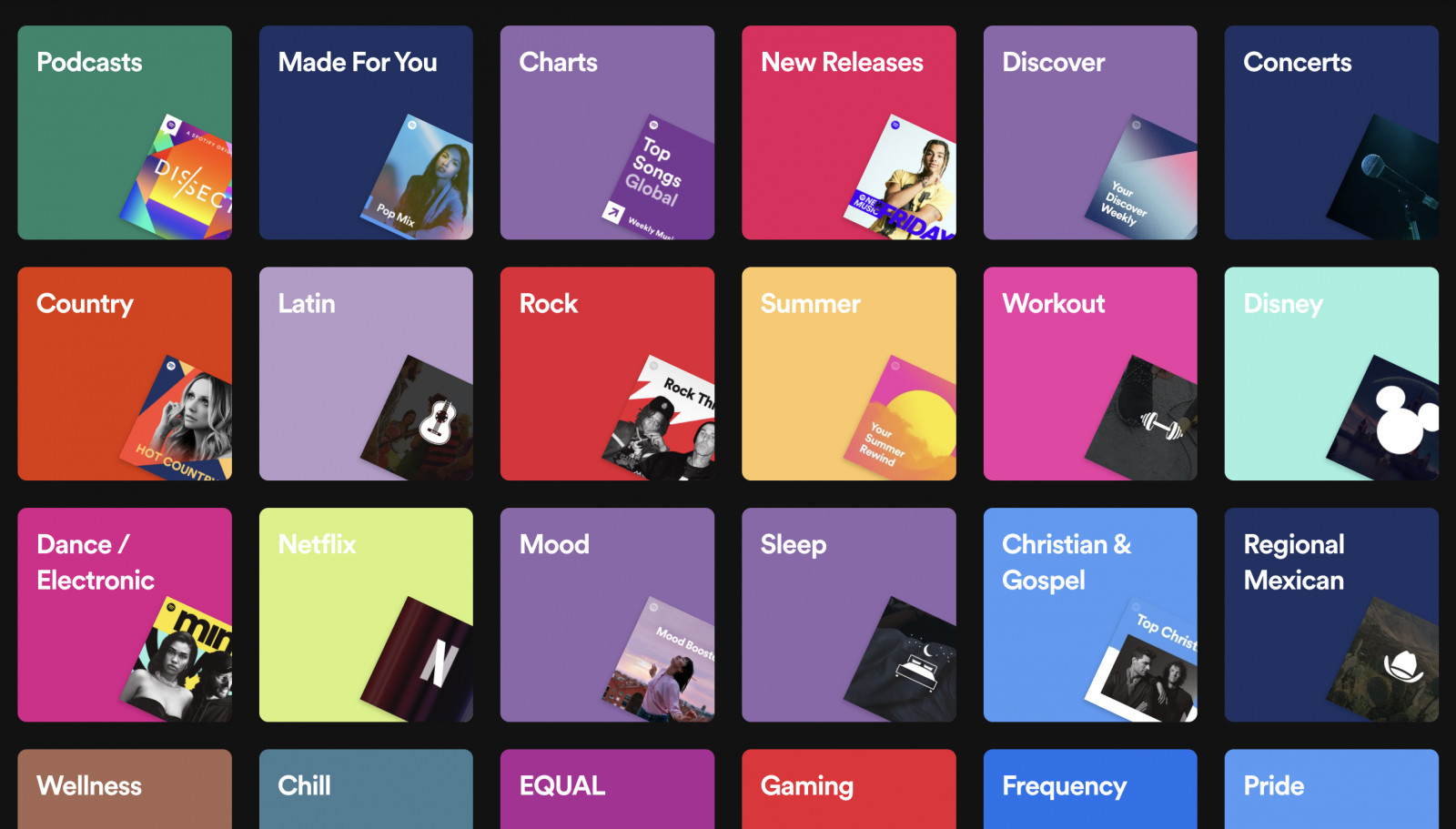

Photo: Spotify Explore

We have heard it (and said it) many times before: the music industry has never been as competitive as it is today. But the challenge is not just that today’s landscape is ultra-competitive, it is also that new artists chasing success are competing against artists who came up before the landscape became so fragmented, as well as the entire history of music — not just that which is new.

In short, new artists today face unprecedented challenges because there are two half-lives being extended at once: the half-life of pre-streaming cultural moments, and the half-life of songs.

Pre-streaming cultural moments last longer

Streaming levelled the playing field, by giving smaller and independent creators a chance to build listener bases without traditional gatekeepers. But, by now, the second-order impacts of streaming are hitting hard. With the barriers to entry significantly lowered, the landscape is oversaturated, listening is hyper-fragmented, and increasingly sophisticated personalisation algorithms (like on TikTok) push listeners further into niches. This is not even to mention the attention recession. It is harder than ever to have a mainstream impact.

All this change has happened in the span of roughly a decade, so there are now three classes of artists all competing in the same arena — but playing by very different rules:

The artists who rose to prominence pre-streaming (e.g., Beyoncé, AC/DC). These artists are able to dominate today because they built their fanbases in much simpler, less congested times

The artists who rose to prominence in the early days of streaming (e.g,. Drake, Ed Sheeran, Taylor Swift). These artists got all of the benefits of streaming’s democratisation of the industry, without all of the second-order impacts

The new artists who are chasing success today. These artists face the biggest obstacles — they are not only competing in an era of ultra-fragmentation, but the artists in classes 1 and 2 are their competitors

Featured Report

Defining entertainment superfans Characteristics, categories, and commercial impact

Superfans represent a highly valuable yet consistently underleveraged audience segment for the entertainment industry. What drives this disconnect is the fact that – despite frequent anecdotal use of the term – a standardised, empirical definition remains absent, preventing companies from systematically identifying, nurturing, and monetising th...

Find out more…

Pre- and early-streaming era cultural moments — like Drake’s Take Care album, Beyoncé’s ‘Single Ladies’ music video, or Nirvana’s whole career — are lasting longer, and are remembered better. This is part of what allows acts like My Chemical Romance and Rage Against the Machine to plot international arena tours today. As Trapital’s Dan Runcie noted this week, rather than just older hits like Kate Bush’s ‘Running Up That Hill’ making a comeback, “the more accurate narrative of catalog success is that ‘people haven’t stopped listening to Drake’s Views or Taylor Swift’s 1989.’ Drake, Taylor Swift, Ed Sheeran, and Adele are the last generation of artists who rose up before the streaming era took off”. For any artist entering the landscape now, it is nearly impossible to create a cultural moment, and harder still to sustain one. The current music landscape is like throwing Michael Jordan, Lebron James, and a high-school NBA aspirant onto the court at the same time. The aspirant may eventually make it to the NBA, but the hall of fame is increasingly out of reach.

In the streaming era, songs have longer half-lives

In the pre-streaming world of linear media, the industry could measure only the initial sale of music. It did not matter whether the purchaser went home and played a CD nonstop for the next five years, or threw the CD in a drawer and never looked at it again, because post-sale consumption could not be measured. As such, the music industry has always been geared towards promoting what is new and pre-streaming, music by new artists did not compete with previous releases (at least when it came to driving revenue).

That has all changed in the streaming era, where every instance of music consumption is measured (and monetised). Streaming also makes it easier for listeners to find older music, and personalisation algorithms recommend music regardless of its age. The result is that the revenue profile of a song can extend far beyond the 18-24-month break point, when it is considered “catalogue”. In other words, new music competes not just with other new music, but with everything that has ever been released — and that list is growing every day.

A field of all levels

Even though the barrier to entry for music-making and distribution is lower than ever, new artists today face two seemingly insurmountable barriers that are unique to them:

Competing with pre-streaming-era superstars

Competing against all of the music in history, not just new songs and artists

Both of these issues are only amplified by the astounding amount of new music being released every day. So, while the playing field is level in theory, it may be better described as a field of all levels — all competing against one another, with an endless and ongoing supply of new entrants to the arena. Of course, in the pre-streaming era, many of today’s artists would not have had a shot at all, so even today’s hyper-competitive landscape may be preferable to what it was like before. Today’s artists are also shifting their definitions of success — deprioritising fame, while prioritising remuneration and niche fanbases. The wider music industry will have to recalibrate its definition of success, too.

Look out for MIDiA’s upcoming August report, ‘Scenes: A new lens for music marketing’, which tackles these issues and more.

There are comments on this post join the discussion.