Why Netflix Can Turn A Profit But Spotify Cannot (Yet)

Having just celebrated its 10th (streaming) birthday, Netflix followed up with a strong earnings release, announcing 5.8 million net new paid subscribers in Q4, sending its share price up by 9%. This wraps up a stellar year for Netflix, one in which it doubled down on original programming and delivered acclaimed hits such as Stranger Things and The OA, shows that don’t fit the traditional TV mould. In fact, Stranger Things was turned down by 15 TV networks before finding a home at Netflix and The OA’s oscillating episode lengths (from 1 hour 11 mins to 31 mins) would have played havoc with a linear TV schedule (not even considering its mind bending plot).

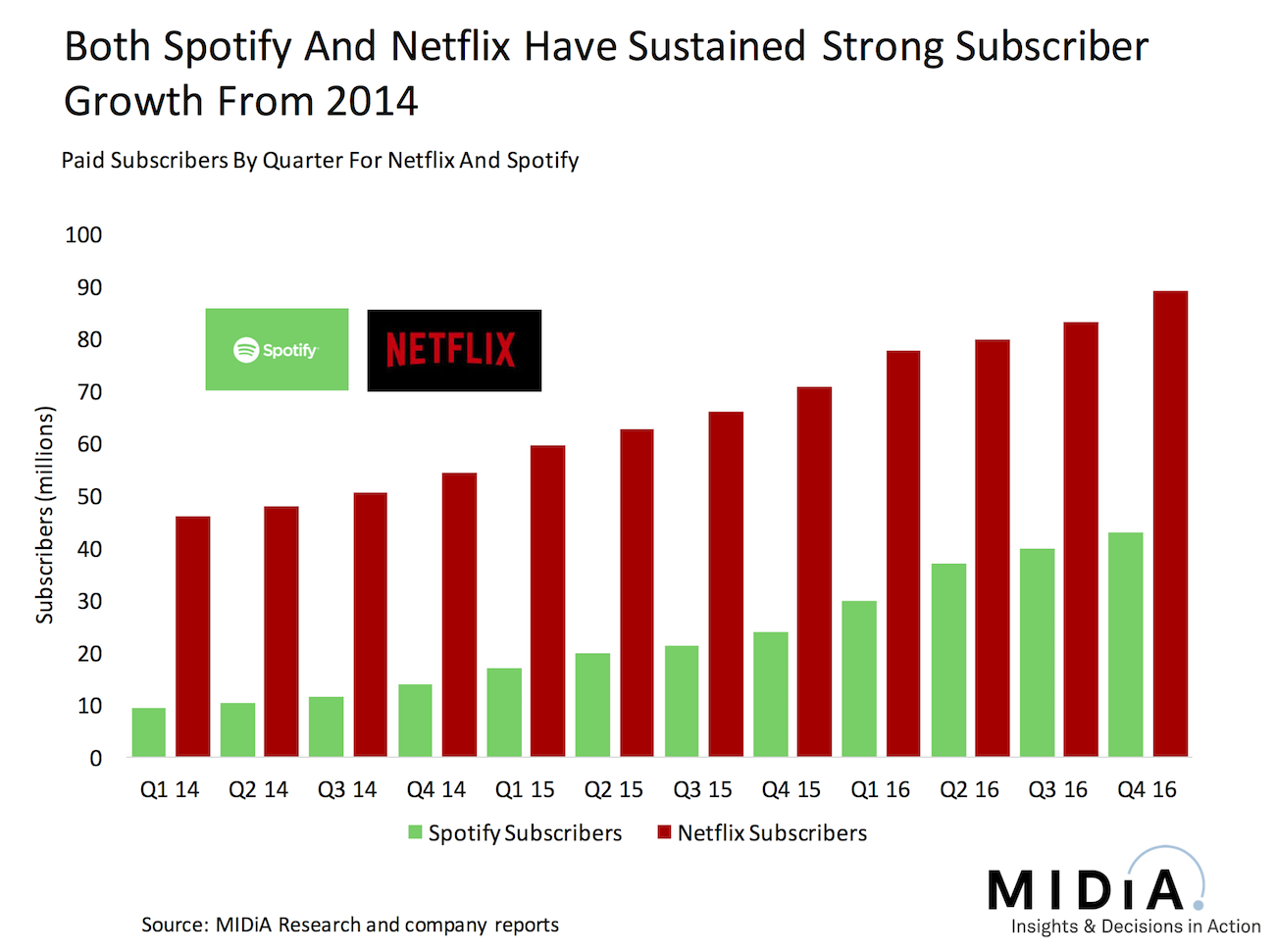

Netflix closed 2016 with 89.1 million subscribers and the temptation to benchmark against Spotify’s equally strong year is too strong to resist. Spotify (which celebrated its decade in June 2016) closed the year with around 43 million subscribers, 48% the size of Netflix. But a closer look at the numbers tells another growth story.

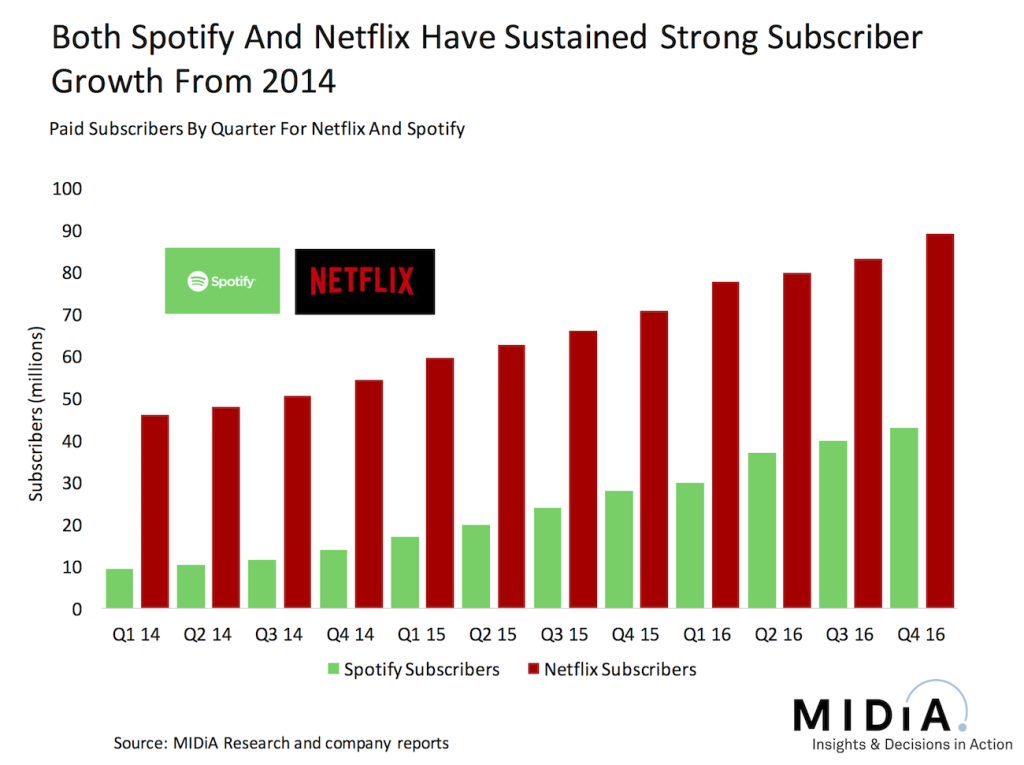

In terms of net new subscribers (i.e. how many more paid subscribers there were at the end of the year compared to the year before) Spotify added just under a million more subscribers than Netflix did in 2016. This is the first time that Spotify’s growth has exceeded Netflix’s (in absolute terms, not percentage terms). While Netflix’s 5.8 million net new subscribers in Q4 2016 was impressive, it followed two much smaller quarters (2.2 million, 3.4 million) and its average quarterly growth for 2016 was 4.6 million. Spotify’s growth by contrast was much more consistent, and higher, averaging 4.8 million. (Note that Netflix reported 7.1 million net new subscribers, however this includes 1.2 million trial subscriptions).

In way of context, Netflix’s core territory (the US) is nearing saturation, adding just 14 million net new subscribers in Q4 2016. The US now accounts for 54% of Netflix’s growth. So Netflix has a more mature user base than Spotify’s. However, Netflix is aggressively pursuing international growth and it has acquired debt to do so. It raised $400 million in 2014 (largely earmarked for European expansion) and a further $1 billion in 2016 (to fund originals and international growth – including international originals and programming). When Spotify raised an additional $1 billion it sent shockwaves through the music industry. When Netflix did it, the TV industry’s reaction more closely resembled gentle (albeit concerned) ripples. Another interesting music / video comparison: in response, Amazon announced it was expanding to 200+ additional markets to its existing 5 in December. Very reminiscent of Deezer’s 200+ markets roll out in response to an increasingly competitive Spotify back in 2011.

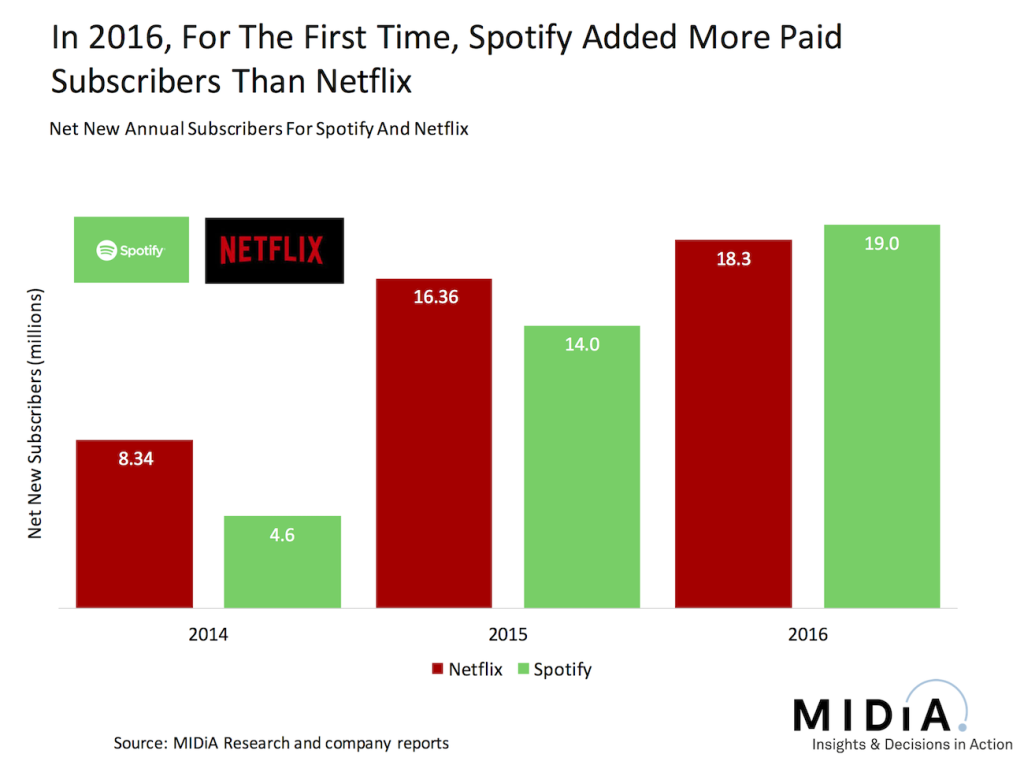

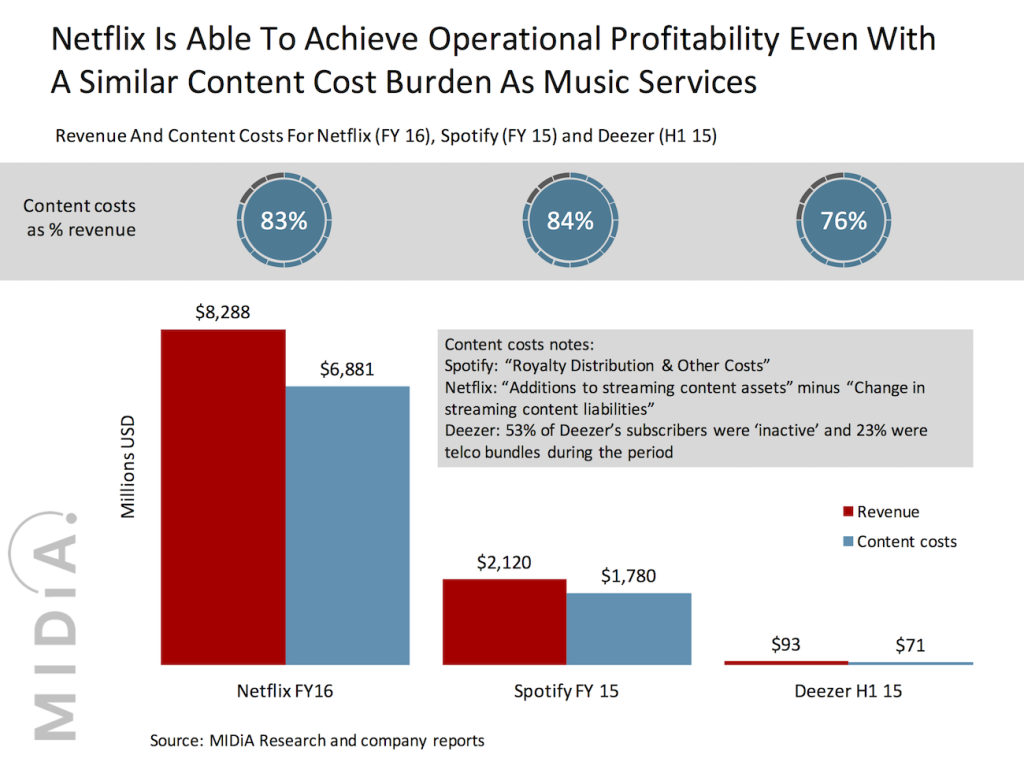

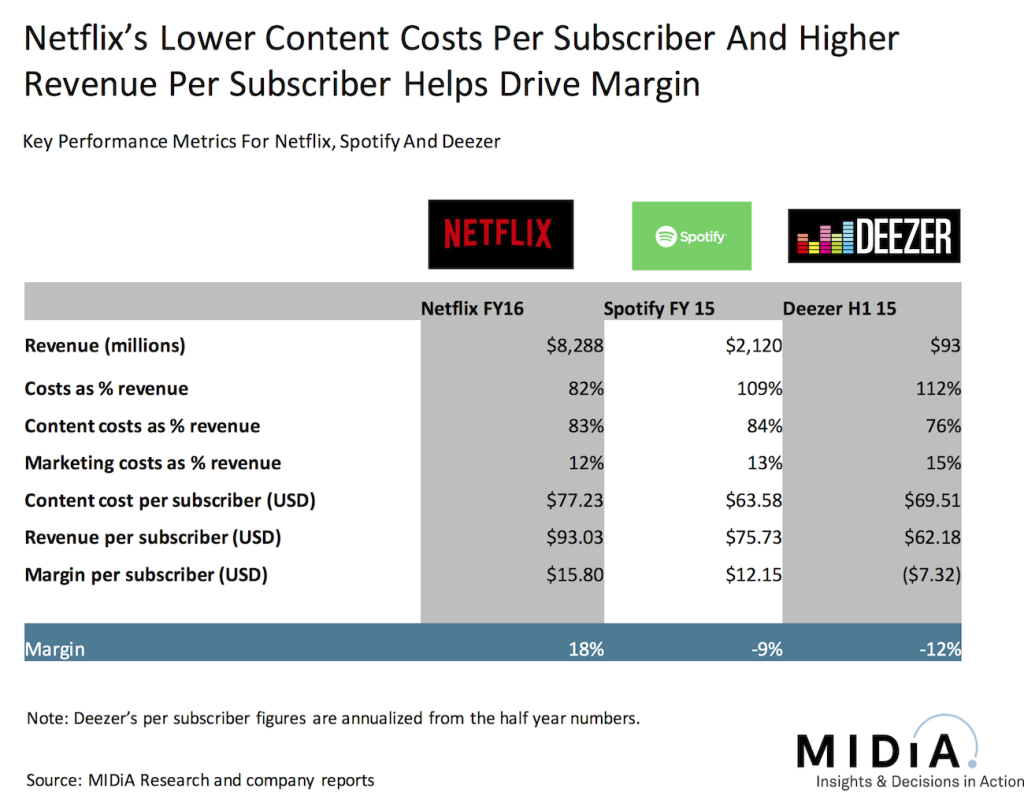

One of the festering wounds of the streaming music business is commercial sustainability. All the key streaming services are either losing money or are part of a bigger company (which absorbs the losses). Netflix, by contrast, posted an 18.5% streaming margin for 2016. Content is the biggest cost for Spotify and co, but interestingly they are in line with Netflix’s content costs. Looking at Netflix (FY 16), Spotify (FY 15) and Deezer (H1 15) content costs as a % of revenue is broadly similar. Deezer’s costs are lower as a share, reflecting the fact that so many of its ‘subscribers’ were inactive during the period (53% of the total).

So why can Netflix achieve an 18% streaming margin, yet Spotify -9% and Deezer -12%. (Note: Netflix reported a 20% overall margin, but this includes the much higher margin legacy DVD rental business). The reason for the difference between music and video streaming quite simply boils down to the way content costs are structured. Minimum Revenue Guarantees (MRGs) are a key factor for streaming music services, as this entails the services guaranteeing to pay for anticipated subscriber growth. If they miss the numbers they still pay, but even if they hit them it means they are always paying against tomorrow’s numbers, not today’s, which is damaging on a cash flow basis. The variance can be highly unpredictable. Deezer wiped off 85% of its gross operating margin in 2014 (compared to 2013) with ‘unused minimum guarantees on rights’.

Free users also add a significant rights burden to freemium music services and dilutes revenue. Thus Spotify’s revenue subscriber is $75.73 compared to $99.03 for Netflix, despite it having a $9.99 price point compared to Netflix’s $7.99.

But the main reason for Netflix’s stronger position is that it owns so much of its content, while Spotify and co rent their content. This means that Netflix is able to employ a series of sophisticated accounting techniques to make the company more profitable. Netflix’s original shows are a balance sheet asset and so can have costs amortized and offset to help profitability. (eg Netflix has a cash flow line item 'Amortization of streaming content assets' for +$4.8 billion).

So where does this all leave us? Who is the winner? Music or video? Spotify or Netflix? Fundamentally both services are growing at impressive rates and have much to be proud of with regards to their respective 2016 performances. Overall, business dynamics are broadly similar, but Netflix’s original content strategy is delivering it a competitive advantage, both in terms of being able to differentiate and in terms of accounting. Of course, the music and TV businesses are dramatically different and Spotify cannot simply ‘do a Netflix’. Nonetheless, Netflix builds a compelling case for original content strategy. The record labels are undoubtedly wary of streaming services becoming record labels themselves, but this might just be Spotify’s route to profitability.

There are comments on this post join the discussion.