What Spotify Can Learn From The Roman Slave Trade

OK, you’re going to have to bear with me on this one, but let me take you back to 2nd century Rome…

The Roman Empire was at the peak of its powers. Its borders stretched from Scotland down to Syria and across to Armenia, and throughout its dominions, Rome spread its culture, language, administration and military prowess. It brought innovations such as under floor heating, running water, astronomy and brain surgery, but the consensus among many modern day historians is that the Roman Empire could have been much more. Rome was fundamentally a military, expansionist state. Its endless conquests produced a steady flow of captured people that fuelled Rome’s most important economic interest: the slave trade. By the mid 2nd century around one in four Romans were slaves. It was common for wealthy citizens to have 40 or more household slaves, while the super-rich had hundreds.

The importance of economic surplus

The problem was that the over-supply of labour meant wages were horrifically low for the masses, while the rich over spent on slaves to keep up with the neighbours. The net result was that the Roman Empire was not able to create an economic surplus across its population, which meant there was insufficient investment in learning, science and culture. If that surplus had been created, Rome would have spawned a generation of innovators, inventors and entrepreneurs that should have created an industrial revolution. This raises the tantalizing possibility of steam power and steel having emerged before the middle ages, which in turn could have meant that today’s technology revolution might have happened hundreds of years ago, and not now.

Instead, the Roman Empire eventually crumbled with Europe forgetting most of Rome’s innovations – paved roads weeding over, aqueducts running dry and heated floors crumbling. We had to wait until the second half of the 18th century for the Industrial Revolution, for the change, which crucially followed and overlapped with the Age of Enlightenment. It was a period of learning unprecedented since the Renaissance (when everyone busied themselves relearning Rome’s lost secrets), which was fuelled by Europe’s economies developing sufficiently to create enough surplus for more than just the aristocracy to learn, invent and create.

So, Rome inadvertently held back human progress by half a millennium because of its obsession with slaves. But what does that mean for Spotify? The key lesson from the Roman experience is that being saddled with too large a cost base may not prevent you from growing big, but it will hold you back from fulfilling your potential and from building something truly lasting. You can probably tell now where I am heading with this. Spotify’s 70% rights cost base is Rome’s one in four being slaves.

Product innovation where are you?

Spotify has made immense progress but it, and the overall market, has done too little to innovate product and user experience. There’s been business and commercial innovation for sure, but looking back at the streaming market as a whole over the last five years, other than making playlists better through the smart use of data and curation teams, where is the dial-moving innovation? Where are the new products and features that can change the entire focus of the market?

Compare and contrast how much the likes of Google, Facebook and Amazon have changed their businesses and product offerings over that period, streaming just got better playlists. Musical.ly shouldn’t have been a standalone company, it should have been a feature coming out of Spotify’s Stockholm engineering team. But, instead of being able to think about streaming simply as an engine, Spotify has had to marshal its modest operating margins around ‘sustaining’ product development, marketing and customer acquisition.

Post-listing scrutiny

Spotify will likely go public sometime next year as a consequence. However, once public, it will need to deliver demonstrable progress towards profit with each and every quarterly SEC filing. Growth alone won’t cut it – just ask Snap Inc. Spotify does not have a silver bullet but it does have a number of different switches it can flick that will each contribute percentages to net margin. Collectively, they can help Spotify become commercially viable and, in turn, enable it to invest in the product and experience innovation that the streaming sector so crucially lacks. Spotify hasn’t done these yet because most of the moves will antagonize rights partners, but it will be left with little option.

Spotify the music company

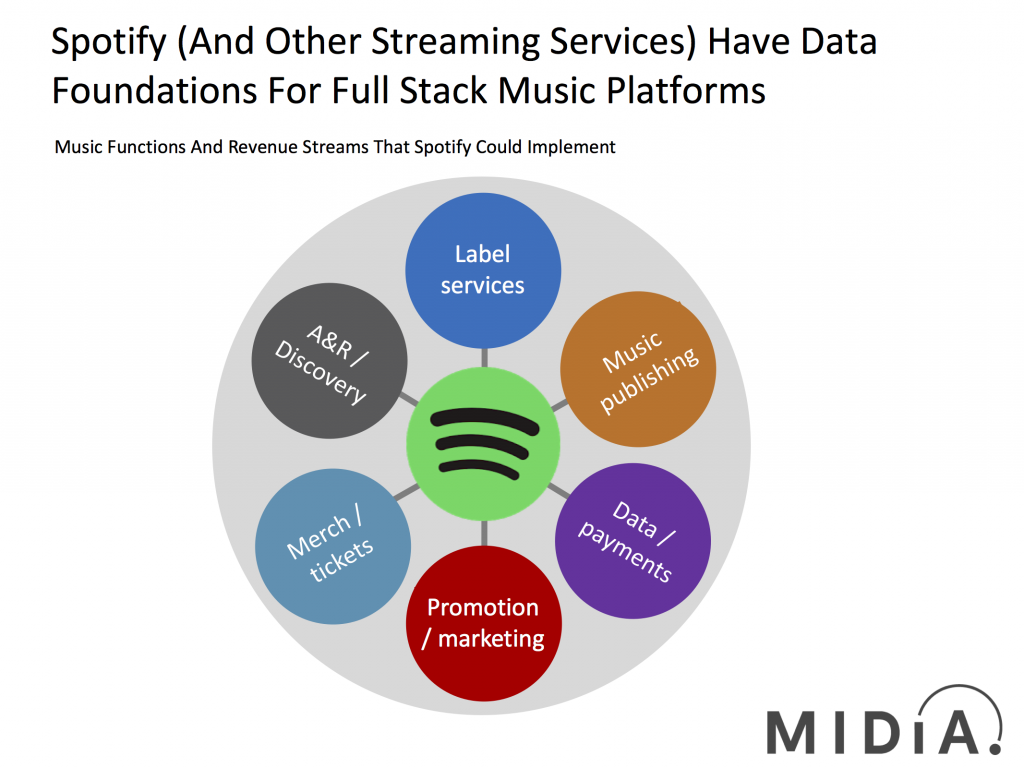

To say that Spotify will become a label is too narrow a definition of what Spotify could become. Instead, it would be a next generation music company, encompassing master rights, publishing, A&R, discovery, promotion, fan engagement and data, lots of data. If Spotify can get a couple of good quarters under its belt post-listing, and maintain a high stock price, then it could go on an acquisition spree, gaining assets for a combination of cash and stock. And, the bigger and bolder the acquisition the more its stock price will rise, giving Spotify yet more ability to acquire. This is the model Yahoo used in the 2000s, with apparently over-priced acquisitions being so big, as to impress Wall Street enough to ensure that the increase in market cap (i.e. the value of its shares) was greater than the purchase price. Spotify could use this tactic to acquire, for example, Kobalt, Believe Digital and Soundcloud, to create an end-to-end, data-driven discovery, consumption and rights exploitation music power house.

What other ‘label’ could offer artists the end-to-end ability to be discovered, have your audience brought to you, promoted on the best playlists, given control of your rights and be provided with the most comprehensive data toolkit available in music? And of course, by acquiring a portion of the rights of its creators, though not all, (that’s where Kobalt / AWAL come in) Spotify will be able to amortize some of its content costs like Netflix does, thus adding crucial percentages to its net margin. It will also be able to carry out Netflix’s other trick, namely using its algorithms to over index its own content — again adding crucial percentages to its margin.

Streaming is the engine not the vehicle

The way to think about Spotify right now, and indeed streaming as a whole, is that we have built a great engine, but that’s it. We do not have the car. Streaming is not a product, it is a technology for getting music onto our devices and it is a proto-business model. While rights holders can point to areas where Spotify is arguably over spending, fixing those will not be enough on their own, it needs to accompany bolder change. Once that change comes in, Spotify can start to fulfil its potential, to become the butterfly that is currently locked in its cocoon. While rights holders will be understandably anxious and may even cry foul, they have to shoulder much of the blame. Spotify simply doesn’t have anywhere else to go. Unless of course it wants to end up like Rome did....overrun by barbarians, or whatever the music industry equivalent is...

There are comments on this post join the discussion.