We need ‘real’ artists for the return to reality

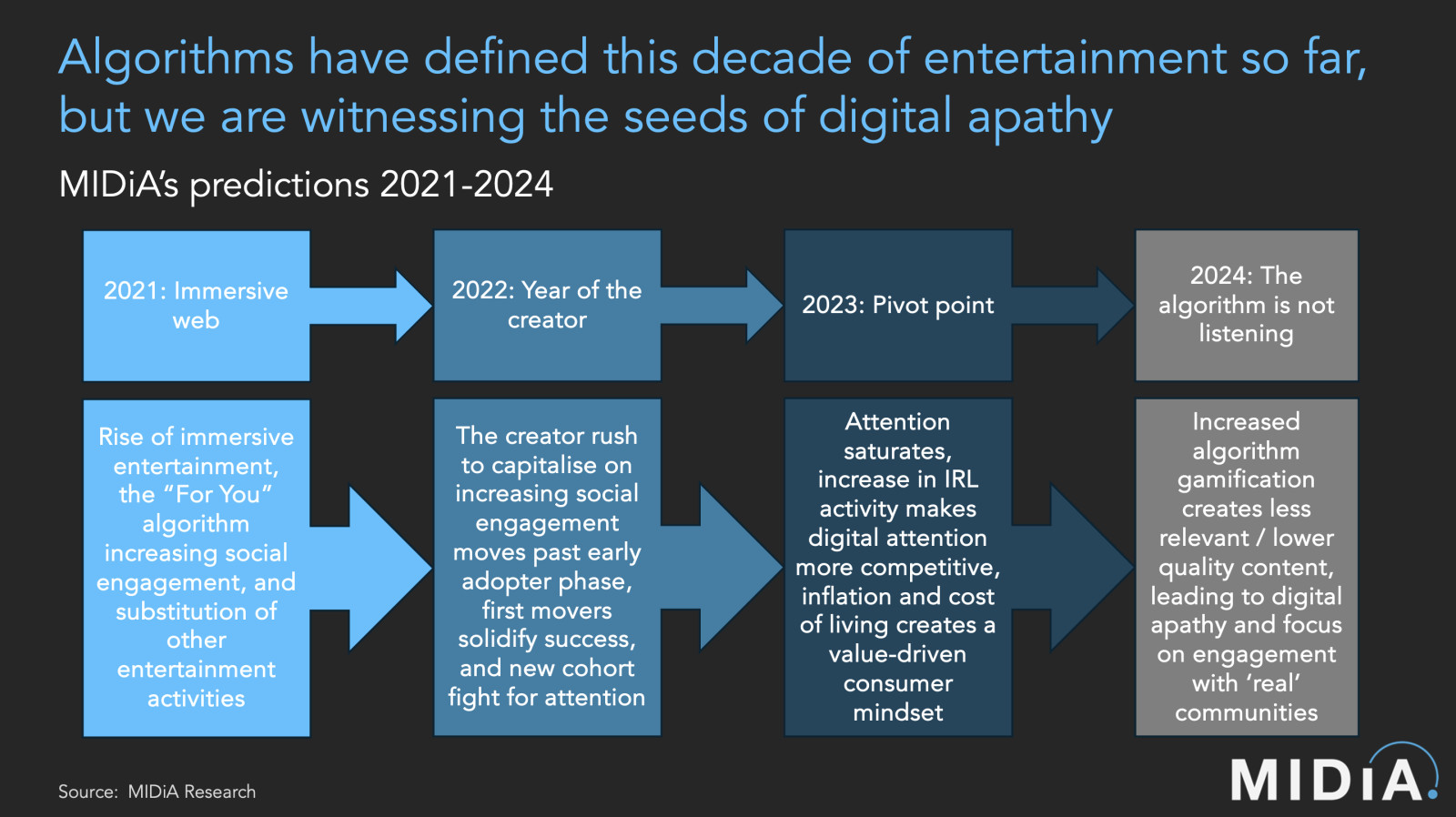

The big theme of MIDiA’s 2024 predictions is that ‘the algorithm is not listening’. A third of the way into the year, we are seeing more and more evidence that this is the case. The past few years have seen social media feeds become hyper-personalised to the point where algorithms now know us too intimately. They have become a warped mirror of our identity, designed to drive engagement. For many, however, this is now too much to bear. Meanwhile, social platforms in their next stage of growth have begun to transition from delivering what users want, to delivering the content which best benefits the platform itself.

Gen Z in particular are increasingly rejecting the algorithm because they simply have no more engagement left to give. The rise in 2000s-era “dumb phones”, which come with only basic calling and texting capabilities, is one example of this. April saw searches for “dumb phones” hit a new peak on Google trends in the US, along with the recent release of “The Boring Phone” from Heineken and Bodega. While this is clearly niche, the 250m+ posts of flip phones on TikTok, certainly show an increasing appetite for a break from the algorithm (despite the irony of using a smartphone to create content around a dumb phone).

On top of this, more and more studies are coming to the fore surrounding the impact of Gen Z’s relationship with social media and algorithms. Jonathan Haidt’s “Anxious Generation” has perhaps been the highest profile, but further research has shown how teenagers see algorithms as reflections of themselves but also leave them vulnerable to distorted self-images that can lead to serious mental health problems. It is no wonder that younger generations are increasingly less trusting of the algorithm, incentivising entrepreneurs to launch new algorithm-free platforms.

More, more, more

Younger consumers in particular are hyper-aware of the mechanics of the engine that delivers their content. As a result, they are not only actively engaging with the content they want to see but also actively disengaging from content that does not warrant a place in their feed. It is a constant negotiation, presenting ideas of who we are or what we could be. In exchange, users either accept or reject content as an extension of their identity.

The cognitive load has become overwhelming for many, turning what is presented as entertainment into a daily practice of actively determining who you are and who you aren’t. When the algorithm is a reflection of yourself, every second is a choice, every swipe is a request to establish who it is that you are. And all of this is to serve more engagement for the platform.

Featured Report

Cultural movements A new take on mainstream for the fragmentation era

Entertainment has become nichified, mainstream has become smaller, and audiences have fragmented. While this has been crucial to the rise of the long tail and the creator economy, there is a need for a...

Find out more…If the whole point of social media algorithms is to listen to the user’s input and respond with output that leads to more engagement, what happens when users hit their limit of engagement? In today’s saturated attention economy, there is little room to give any more, but the algorithm simply cannot understand the request for less. Consumers have no option other than to switch off.

The return to reality

This tension was well articulated by the CEO of Patreon’s SXSW keynote on “the death of the follower”. He argues that algorithms have destroyed the direct-to-fan relationship and that following is meaningless when platforms decide what you should and should not see. For artists, this means that even their own followers are not necessarily going to find out about their new show, which means they do not sell tickets and they do not build their careers.

In the past year, we have heard from execs across the business that virality is not delivering real-world results the way it used to. The challenge is that the music industry has become largely dependent on TikTok's virality to move the needle across other metrics. As the Universal takedowns have shown, if TikTok is not delivering value elsewhere, then it better start paying up.

In the meantime, artists cannot build careers if their followers cannot hear them. So how do they reach music fans? The answer is simple: meet them off-screen. MIDiA’s data shows that doing more in-person activities is the most popular way to reduce screen time for music subscribers, vinyl buyers, and gig attendees. Artists need to invest in their ability to perform in the real world if they want to find paying fans.

Music fans are moving on from what the algorithm serves them on their screen. They want “real” artists. It is more important than ever to protect the venues and institutions that create platforms for artists. The Music Venue Trust’s £1 ticket levy is a start. However, if the future of music is around fandom and fan communities then more needs to be done to protect the spaces where communities can gather. If that can be done, then real life might end up being a better entertainment proposition than the algorithm.

The discussion around this post has not yet got started, be the first to add an opinion.