Time to jump off the algorithm highway

Life is perpetual change, so it is perhaps overdoing it to suggest that the music business is at a cultural pivot point. Yet, what comes next has the potential to be looked at, years from now, as a dividing line between before and after. For more than half a decade, the music business has been hurtling down the algorithm highway, repurposing artist development, marketing, fan engagement, and even the structure of the song itself in order to stay the path. Everything is splintering, from attention to remuneration, with creators and rightsholders alike finding themselves feeding a beast whose hunger is never sated. Much like an addict who wants to quit but cannot, the music business understands the problem and the costs it incurs them, yet they dare not jump off the algorithm highway for fear of being left behind by those who do not. And yet, jumping is exactly what is needed, to halt the perpetual commodification of both music and creators. It is a leap of faith, but onto a welcoming crash mat: scenes.

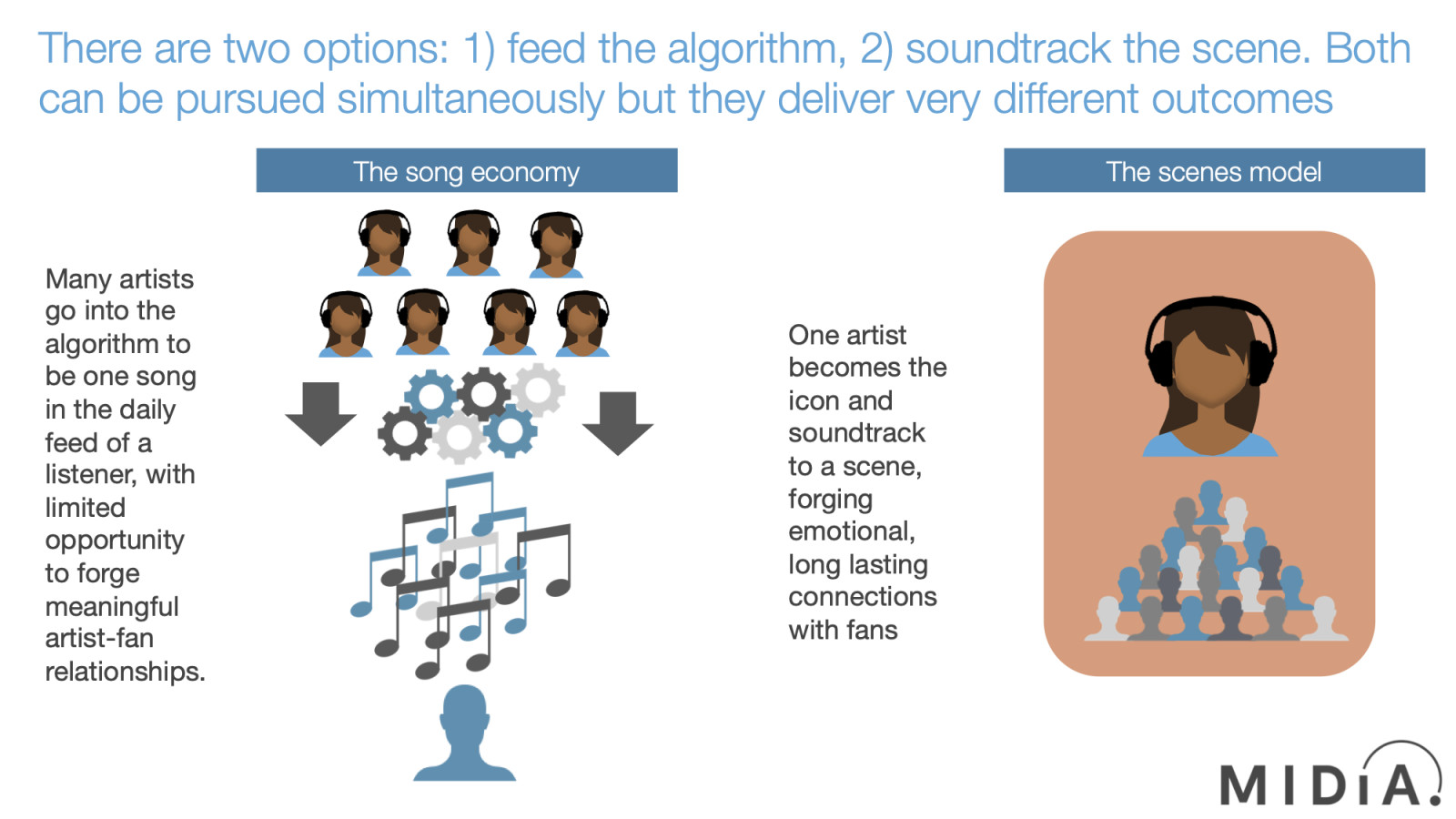

At Future Music Forum this week, myself and fellow MIDiA analysts Tatiana Cirisano and Kriss Thakrar talked a lot about MIDiA’s new research into scenes and identity (MIDiA clients can read our latest report on the topic here). Regular readers will be familiar with our work on fragmented fandom and how the splintering of consumption has created a parallel splintering of culture, with new hits becoming smaller and more short-lived. In this song economy environment, it is the song, not the artist, that is the central currency, thus making nurturing smaller fandoms mission critical. But fandom itself is the symptom, the cause is identity, and this, along with the scenes in which it manifests, is where the future of music marketing lies.

Algorithms have assumed a central role in the success of artists in today’s music business, with marketers forever trying to improve their understanding of their inner workings in order to gain advantage for their artist. It is, in many respects, a fool’s errand, as it is in the platforms’ interest to continually evolve the algorithms in order to ensure it is themselves that determine success, not third parties. Nonetheless, there are ways to succeed in the song economy: you may not be able to beat the algorithm, but you can join it. This means thinking and behaving like an algorithm, to hold virality by the hand. Just like an algorithm, this means real-time multivariate testing within target segments, and progressively expanding only to next-level associated segment, resisting the ability to go big as soon as something fires. But using the algorithm as a marketing discipline truly effectively entails a degree of ruthlessness that many artists and labels would find unpalatable. Algorithms find success by casting out failure instantly, instead only amplifying that which resonates within target segments. So a label pursuing this approach would need to be willing to ditch a campaign incredibly early if it does not, however much the label might believe in the release or however big a priority the artist might be. Artist rosters would become a production line of bets, as quickly discarded as signed. Failing fast is as important as succeeding fast in the song economy.

This ruthlessness does not sit well with the traditional model of building an artist but, as dystopian a vision as it might be, is the exact path that labels already find themselves on. Scenes represent an alternative way forward.

Scenes and identity

Featured Report

Defining entertainment superfans Characteristics, categories, and commercial impact

Superfans represent a highly valuable yet consistently underleveraged audience segment for the entertainment industry. What drives this disconnect is the fact that – despite frequent anecdotal use of the term – a standardised, empirical definition remains absent, preventing companies from systematically identifying, nurturing, and monetising th...

Find out more…

Scenes have always existed, but now there is a growing proliferation of online scenes that allow a degree of specificity that was simply not possible previously. As Tatiana puts it:

“Not only can people find people across the globe with the exact same interests and values, algorithms actually push those people closer together”.

Though scenes can be transitory and ephemeral, subject to fast-shifting cultural trends, the really valuable ones are those that are rooted in identity, that speak to who people are about. The eBoy scene, with Young Blud as an icon, is a case in point, reflecting the values of a tribe that does not identify with the Instagram-perfect archetype of appearance.

These scenes sometimes revolve around music, but most often, music is simply the soundtrack, with a number of artists emerging as icons, not because they have cynically targeted them but because they come from those communities and reflect their values. Fandom is an output of this shaping of identity. It is simultaneously a way of showing how much identity matters to you and of reinforcing that identity. In fact, fandom is identity’s virtuous circle of influence, with people’s fandom reinforcing their identity and communicating it to their scene community, thus reinforcing their bonds within it.

Identity is fandom’s ground zero. Music marketers that are able to identify and nurture it (rather than simply attempt to harvest it) have an opportunity to forge a depth of artist-fan relationship that will endure far beyond the whim of any algorithm, survive both hit and miss singles, and will not disappear into the black hole of lean-back consumption.

Streaming put fandom on hiatus. Scenes represent an opportunity to reforge fandom for the modern era, an incubator for artist careers. In short, an antidote to the song economy.

There is a comment on this post, add your opinion.