The productisation of music rights

News that New York-based Pershing Square Tontine Holdings is planning to acquire 10% of UMG is the latest in a wave of financial transactions in the music rights space. Alongside this, Believe’s impending IPO has the potential to be one of the biggest things to happen to the independent music sector in some time, and comes as part of a wave of IPOs (e.g. WMG, UMG), SPACs (e.g. Anghami, Reservoir) and no end of catalogue funds and acquisition vehicles. This trend, with good cause, has been referred to as the ‘financialisation of music’ but that only captures part of what is at play here. This is more than simply an influx of capital and debt; financial institutions are now becoming part of the plumbing of the music business, and in turn they are changing the definition of what constitutes success. This shift in objectives and desired outcomes has the potential to rebalance how the music industry operates.

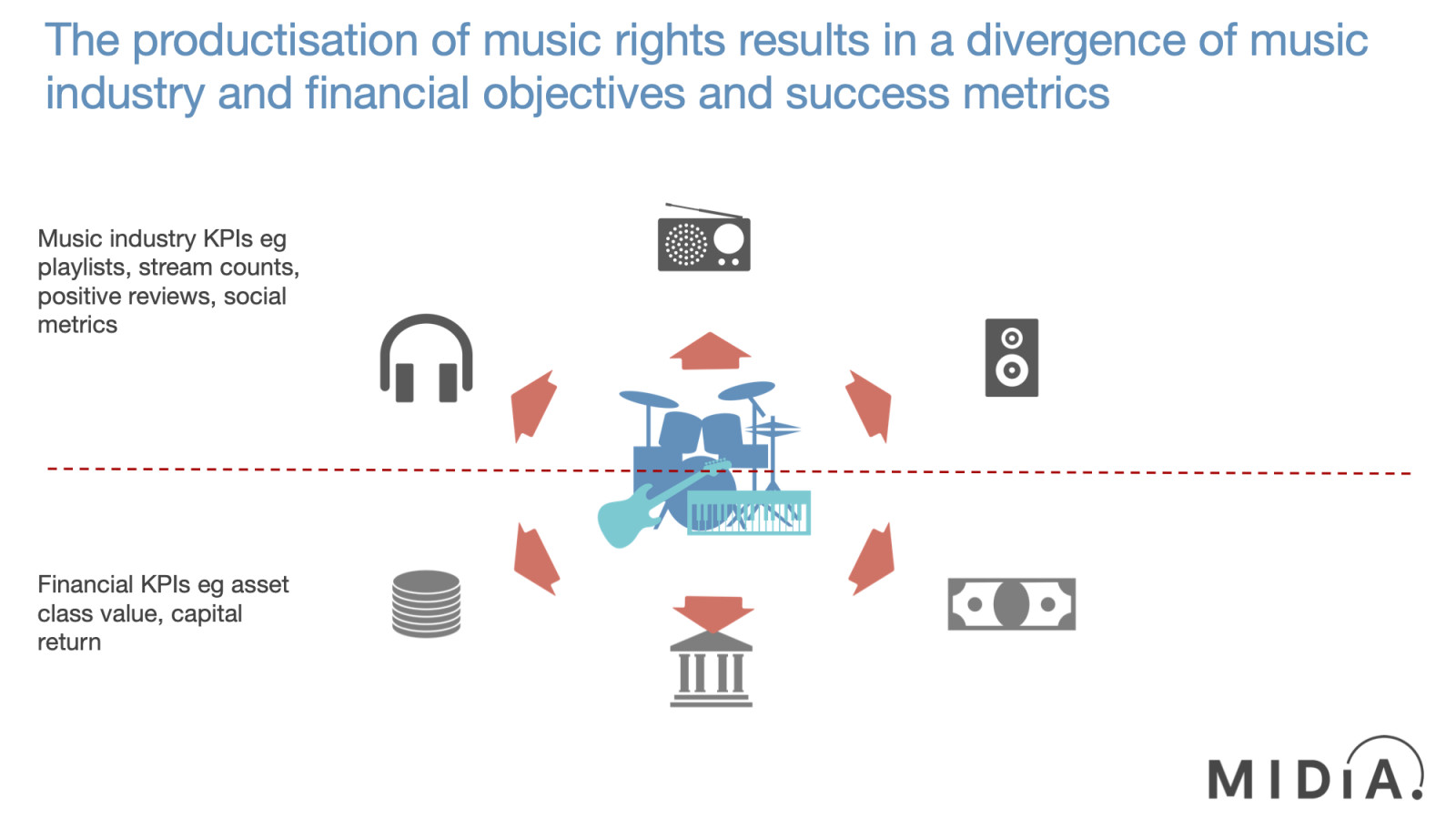

Though the strategies and aspirations of financial entities that are investing in music are diverse, they are usually very different to those held by music companies, particularly those of traditional music rights holders. What constitutes success for one may not matter much for the other. For example, a credible music industry objective (e.g., get playlisted) might have little immediate relevance to asset class value. Even the macro market trends illustrate the disconnect: the value of publicly announced music catalogue transactions grew by 14% in 2020, while global music publisher and label revenues each grew by just 8%, i.e., the financial value of music catalogues grew faster than their ability to generate revenue.

Music rights have become established as an asset class, with their value defined differently than how the music industry typically measures value. The value of a song to the music industry resides in its commercial and cultural performance. A hit is a hit. But that same song’s value as part of a catalogue as a financial asset is also defined by a wider range of factors, including the relative value of music as an asset class compared to other financial asset classes. When entities such as pension funds and investment managers acquire music rights, they add them to diverse portfolios of assets, with music representing a particular tier of risk and return. Those financial institutions accrue value by repackaging the assets in derivative financial products that they then sell on. A pension plan is a straightforward example. This is the productisation of music rights.

This all matters because the strategic objectives of the financial entities will inevitably shape those of the music rights company. For example:

Featured Report

Streaming strongholds High-potential markets for global music players

While the balance of music streamers continues to tip towards global south markets, their smaller ARPU rates limit their revenues. Meanwhile, periodic price-rises and the advent of supremium will reinforce the contributions from the West. This report highlights streaming strongholds, those markets which, underscored by high music engagement and his...

Find out more…· The Tencent-led consortium that acquired 20% of UMG has made a bet on rights versus a bet on distribution (e.g. Spotify) and as such will have a set of views about what UMG’s relationship with streaming services should be. Right now, those views most likely align closely with those of UMG leadership, but if at some stage they were to diverge then UMG’s strategy itself could be affected.

· The Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan’s investment in Anthem Entertainment forms part of an investment strategy that will expect an increase in asset value and return. Depending on the specifics of the strategy, this could, for example, favour Anthem focussing on catalogue acquisition over riskier creative investments in specific songwriters.

Neither of these examples are inherently positive or negative, they simply illustrate that the scale and nature of the investments coming into music rights are also changing how the music business operates. In some instances that will result in conservatism, in others bold opportunism. But the determining factors will be less about the music ethos of the music company and more about the investment thesis of the financial backer.

External finance has long played an important role in the music business, but never before at this sort of scale. Music catalogue M&A transactions (not including IPOs, SPACs etc.) have already reached 74% of what was a record level in 2020. The scale of this inward investment shows no sign of slowing. So, whatever your views on the productisation of music rights, this is a market dynamic that is going to help shape the future of the music business.

There is a comment on this post, add your opinion.