The Attention Economy Has Peaked. Now What?

Regular followers of MIDiA will know that we’ve been writing about the attention economy for a number of years now. Throughout 2019 we have been building the concept that we have arrived at peak in the attention economy – that all of the addressable free time has been addressed. In 2017, Netflix’s Reed Hastings said sleep was his biggest enemy. By 2019 he claimed Netflix was competing more with Fortnite than HBO (it wasn’t really, but the concept of competing in adjacent markets is valid). In the old world, media was nicely siloed by dedicated formats and hardware (print newspapers, books, DVDs, CDs, radio sets). Now, though, we access through devices where everything is separated by nothing more than a finger swipe. Attention saturation was always going to be an inevitability, not a possibility. The important question is not why this happening, but what will come next and what the right strategies are for surviving and thriving in this post-peak world.

A mine full of canaries?

What got MIDiA first thinking about peak attention was seeing the mobile gaming audience declining every quarter in our quarterly tracker surveys. Mobile games were the canary in the mine for peak attention. When we first got mobile phones, we didn’t have a huge amount to do with them. We couldn’t watch our favourite shows, and we couldn’t easily (legally) listen to new music. So many consumers filled their ‘dead time’ by playing games, as they were de rigueur in the early days of the app stores. Before long casual gamers were the core audience of titles like Angry Birds and Clash of Clans, while your middle-aged aunt was spamming you with Facebook invitations to play Candy Crush Saga. Once Netflix, Spotify and others had got traction, however, those casual gamers started reverting to consuming the content they actually liked the most. The result was a long steady decline in the mobile gaming audience. Now, music looks like it may be following suit.

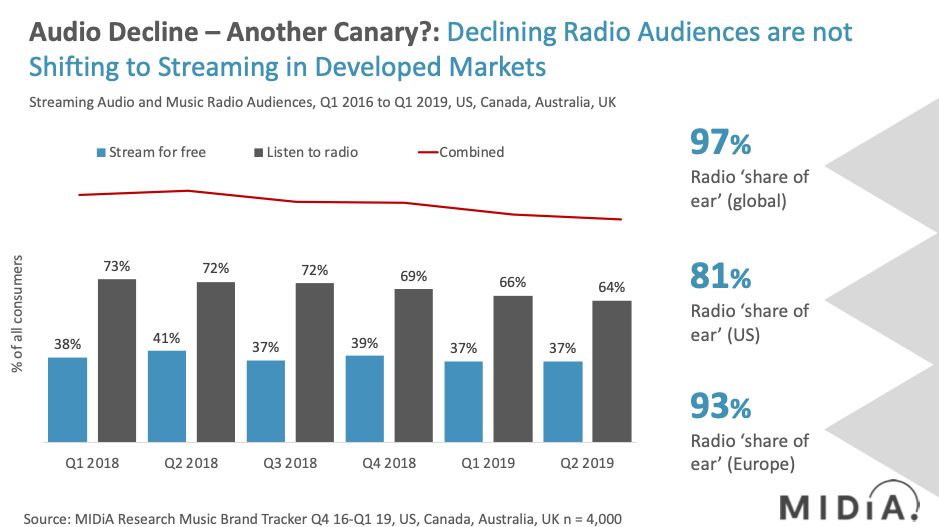

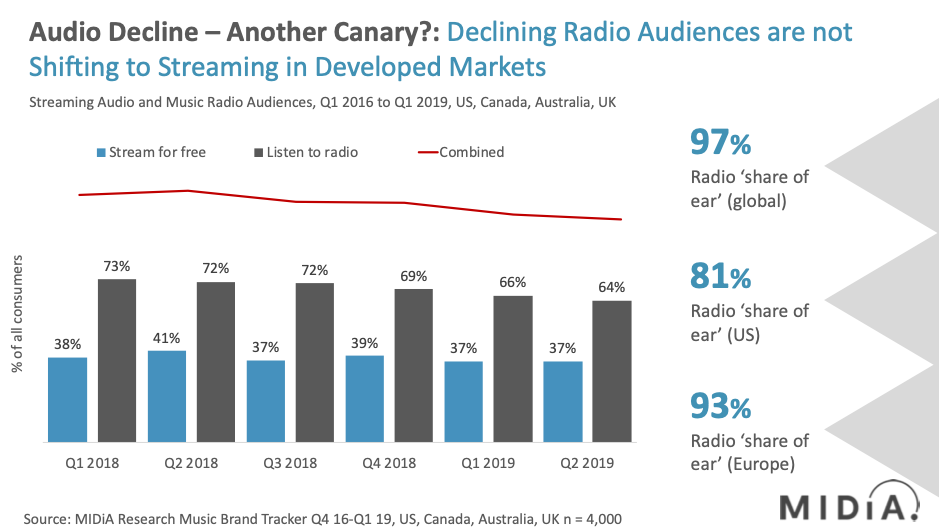

Across the US, UK, Australia and Canada, the share of people that listen to the radio declined steadily between Q1 2018 and Q2 2019. Meanwhile, those streaming audio for free remained relatively flat. The net result is that the combined audio audience declined. So many lapsing radio listeners exited the audio market as a whole (though a share shifted to podcasts, which is not considered in the above chart). The ‘share of ear’ battle is looking a lot like a minor theatre of conflict in a much larger conflagration. Amazon will continue to do a good job of shifting older, high-net-worth consumers to streaming, but that is not enough to stem the tide – especially as Amazon’s global footprint is unevenly distributed.

This is what happens in the era of attention saturation.

Social video is eating the world

Four years ago, MIDiA argued that video was eating the world. Now social video is eating the world. Video is becoming the omnipotent format through which we communicate, consume and share. Social video is eating everything. Captioning looked like it was heralding a new era of silent cinema, but it was in fact a trojan horse – a means of enabling us to fit extra video consumption into our wider consumption patterns. Over time, though, sound has become more important and with the increased tolerance of video we are now far more willing to unmute. Nowhere is this better seen than Instagram and TikTok. Audio is the victim in that equation. Not only are there are many other scenarios where audio is slipping, there are even more scenarios where other media formats are losing out. For example, Epic Games’ decision to allow Fortnite players to watch live video of the Fortnite World Cup while gaming hints at how games companies understand that there is a delicate balance between video extending brand reach and competing directly for gaming time.

Looking back gives us a feel for what comes next

Understanding what comes next in a saturated attention world requires looking back at previous markets that have peaked. The mobile phone and PC markets give us some pointers, but the industrial revolution’s impact on the labour market is an even more useful analogue. Attention is like labour. It is a product of human behaviour and it is scarce. Digital content is analogous to the labour market, and content supply is now beginning to exceed attention output. This is already translating into increased customer acquisition and retention costs.

This is exactly the wrong time for bringing more content to market, but that is exactly what is happening. Nowhere is this better seen that the video subscriptions space with a blizzard-like flurry of new services from Disney, Warner, Apple, Discovery and NBC.

The net result of an over-supply of content is that attention saturation will become an attention deficit for many players, Netflix included. The marketplace needs a new currency for measuring success and monetising audiences.

This is where I am going to cut to credits, leaving you on a cliff edge. For those of you in London next Wednesday (November 20th), come along to our free-to-attend attention economy event, where you can hear my colleague Karol Severin present our attention saturation research and our take on what will be the next audience currency that content providers will need to compete for. For those of you not in London there will also be a live stream, which you will be able to find here at 7pm GMT. Also, check back in next week when I will post the next chapter in this story.

NOTE: I shamelessly sat on the shoulders of giants in this post – these ideas were collectively crafted by the entire, amazingly talented MIDiA team.

The discussion around this post has not yet got started, be the first to add an opinion.