Is Video Streaming About to Witness Music’s P2P Trial by Fire?

As the direct-to-consumer (D2C) big bang moment continues the slow process of expansion through the attention-saturated digital universe, video service providers are struggling with the existential question of how to compete well enough to survive in the hostile environment of overstimulated, wallet-stretched and increasingly tech-savvy consumers.

The strategies behind the drive for differentiation are varied. Netflix first experimented by introducing binge-watching; now the behaviour is mainstream, and its main appeal is that of discovery and breadth of content library. However, new streaming service Disney+ is pulling together Disney’s strong content library to support its episodic original release strategy, as well bundling in ESPN+ for the sports-viewing proposition and Hulu with its established younger base and catalogue of contemporary content.

Larger, traditionally pay-TV media services like Warner Media and NBCU are introducing their own streaming services as well. Warner Media is trying to leverage already-established assets like HBO Max, whereas NBCU is potentially pioneering a truly third-way offering of ad-supported video-on-demand (AVOD) with Peacock.

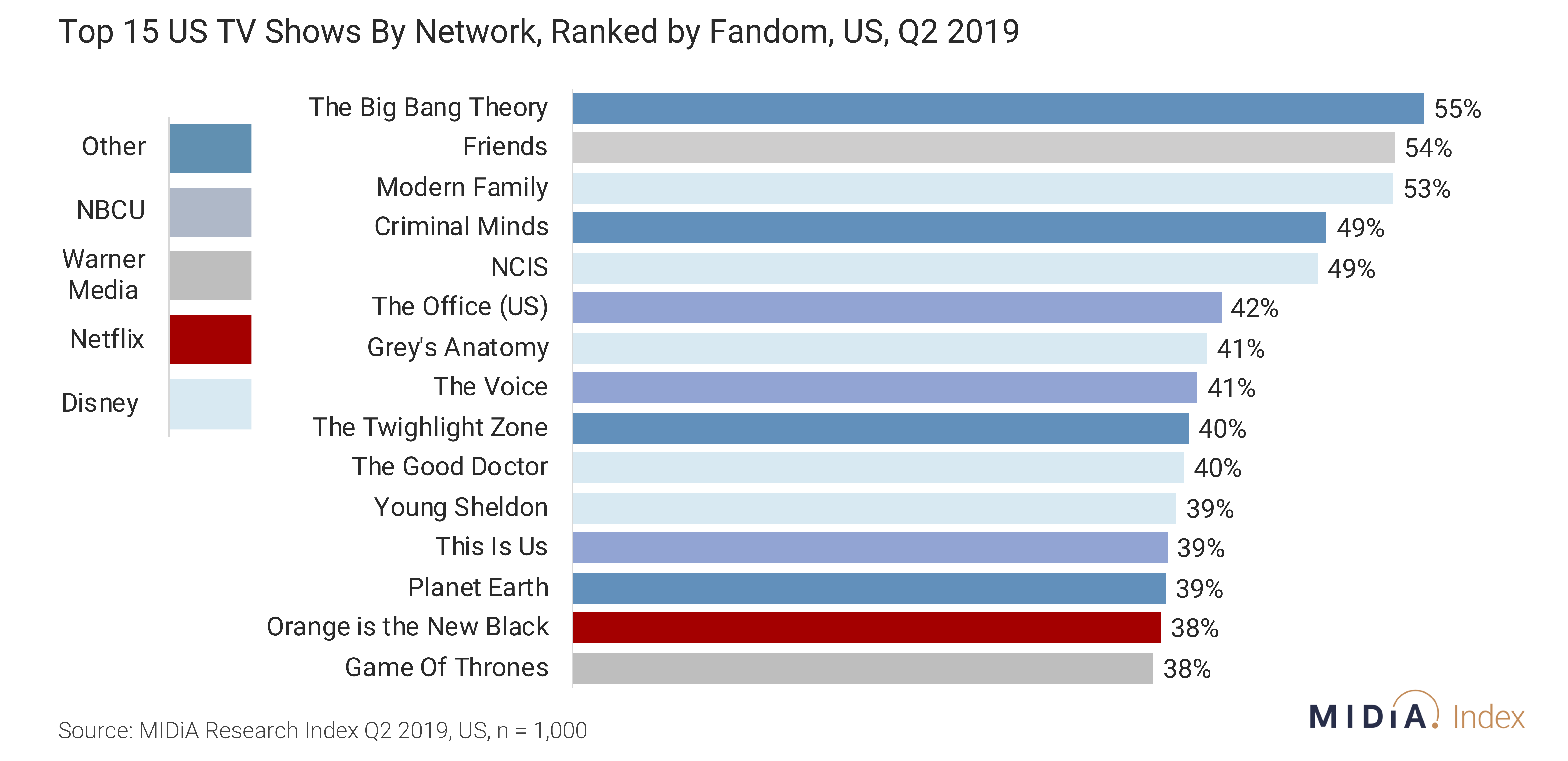

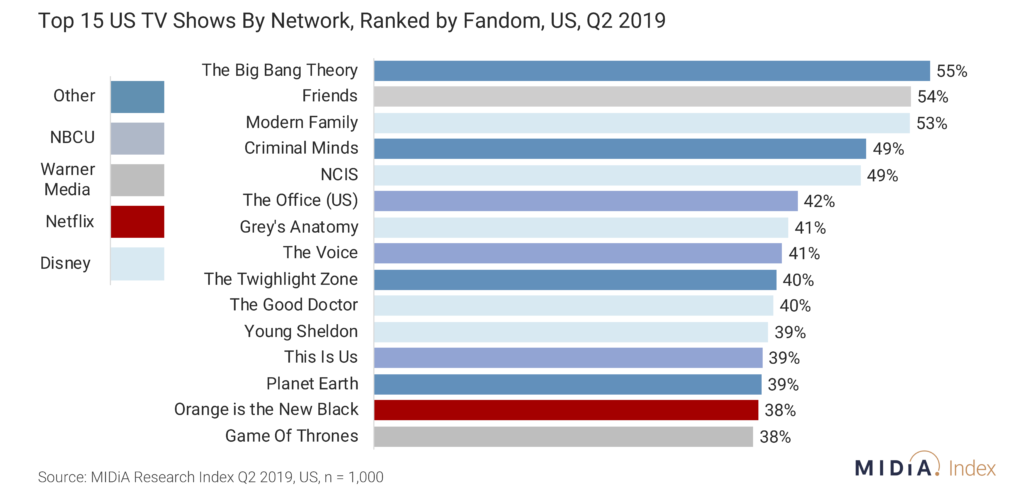

The trouble for consumers is, they’re fans of shows on all of these services – they don’t distinguish between providers, and are even potentially resentful when favourites like Friends or The Office are moved from a service they do have a subscription to, to another where the shows are used as a proverbial carrot to tempt them to take on a new one.

It gets more complicated. Take Friends, for example; soon to move off of Netflix, it will reappear in May on HBO Max, as one of Warner Media’s heftiest assets. Furthermore, it has been announced that a Friends reunion special will be coming to the service, which will likely drive significant uptake on subscriptions by fans of the show as they rush for the new content (whether or not they stay – as with the subscription drop-off following the Game of Thrones finale – is another question).

HBO Max will also be available, however, to YouTube TV members – expanding the reach of the shows but raising questions around the monetisable aspect of subscriptions. Meanwhile, Jennifer Aniston, herself an asset closely linked to the Friends franchise, is headlining The Morning Show on Apple TV+. This means fans with one subscription might be tempted to stay on a service they already have, if it contains a similar enough offering.

Another example: It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia is available on Netflix now, but fans of the show might be appeased by the new show from the same creators on Apple TV+, Mythic Quest: Raven’s Banquet. Or, they might be tempted to stick with that new show’s thematic relative Silicon Valley on HBO.

Featured Report

MIDiA Research 2026 predictions Change is the constant

Welcome to the 11th edition of MIDiA’s annual predictions report. The world has changed a lot since our inaugural 2016 edition. The core predictions in that report (video will eat the world, messaging apps will accelerate) are now foundational layers of today’s digital economy.

Find out more…What is happening here?

As content becomes divided amongst a multitude of services, each scrambling to find the right balance of distinctive appeal and experimenting with new ways of serving content to reach and retain the most viewers, consumers are faced with choice after choice to attain access to content they like and want. While on the surface the inevitable subscription stacking appears to be a return to the era of expensive cable packages, a look at the music industry and its trajectory over the past two decades is perhaps more insightful.

The music industry has traditionally monetised ownership – physical sales – and experiences, i.e. live performances. The digital era, however, had a massive impact: it enabled peer-to-peer piracy. Consumers no longer had to pay to build their own catalogues of music; they could simply download it from the internet. As Spotify and YouTube emerged and developed the scene with label support, consumers shifted back to “legitimate” channels – but the driving value of content had irrevocably shifted from ownership to access. The dominant music streaming services remain successful, despite competition between them, because they all contain robust catalogues with very few, if any, limitations. The music labels, with their priority of enabling success for their creators, have been able to adapt to this, despite monetisation struggles – many of which have emerged alongside the rising capabilities of independent artists themselves.

The dynamic of the video marketplace has its fundamental differences. Requiring big budgets to make, a rise of independent high-quality productions of the same calibre as big studios is unlikely; Netflix is, perhaps, the closest to being the Spotify of the video world in the sense of allowing for a wider variety of productions, all of which it can fund to some extent and many of which come from smaller, independent studios. However, as of yet its discovery capabilities have limited the access to niche fan audiences which has enabled the rise and diversification of independent productions to the extent it has in music – but the successes of Stranger Things and The Witcher point to promise here.

Further, TV and film have always monetised access; from paid channels to DVDs to movie theatre tickets, and now to subscription services, consumers are accustomed to continually paying for access to video. Nevertheless, the potential for free access lurks beneath the established norm; while video downloads fifteen years ago in the era of piracy were not exactly high quality, HD 1080p streams on piracy file hosting sites such as Putlocker mean that, in a pinch, a consumer without a subscription can still get access to whatever show they like in arguably equal quality to what they would otherwise pay for.

The propositional combinations of similarities and distinctions to already-popular content could be enough to keep consumers within specific service ecosystems. However, as content is divided and multiplied and the unique value proposition of video itself declines through oversaturation, platform-agnostic consumers will inevitably find that the subscriptions for the total access they are currently accustomed to become excessive.

With a potential recession, it is unlikely that rational, tech-savvy consumers who already do not have enough hours in their days to watch all the content they like to begin with will stack subscriptions to the point of paying the equivalent of an $80/month cable package. The risk is that they will likely choose one or two key subscriptions, and find free ways to stream the rest – and because of the digital environment, this capability will always be just one step ahead of protections rights holders can use to clamp down on the phenomenon.

The boom of quality content production means this is a great time for video, but it also means a new era of video piracy could be just around the corner. If video intellectual property holders are not careful, they could push consumers into this early through their exclusive D2C partnerships. If, however, they navigate more carefully and considerately – as with Peacock’s minimally-priced, ad-supported service, they can maintain usage and relevancy. D2C video will need to tread carefully in this new environment.

The discussion around this post has not yet got started, be the first to add an opinion.