Hold or twist? The music industry’s innovation dilemma

As Clayton Christensen identified in The Innovator’s Dilemma, there are two types of innovation: sustaining innovation and disruptive innovation. Sustaining innovation is what companies do to enhance existing business models, while disruptive innovation is typically driven by new entrants – insurgents looking to make markets by turning established ones upside down. Of course, if they are successful, eventually they switch to sustaining innovation, too. Streaming is now at the ‘you were the future once too’ stage. In the West at least, the focus is now firmly on optimisation. This is all very sensible and absolutely the safe thing to do. However, music innovation must go beyond simply fine-tuning existing models. As it stands, streaming is perfectly poised for disruptors to come along and turn it upside down.

Sustaining innovation is how more growth will be extracted from streaming. Subscriber growth is slowing in the West. Because this is where majors have most market share (MIDiA’s “State of the independent music economy” report found that majors’ market share in ‘Rest of World’ is just 31%) and most revenue, it is where they are focusing their optimisation efforts. Thus far, this innovation has taken the form of streaming price increases, two tier licensing, and the forthcoming superfan tier (per TechCrunch). Of course, you could make a case that a superfan tier is disruptive innovation, but that will depend upon whether it really pushes the boundaries of what streaming is. Otherwise, it may only be as ‘disruptive’ as mobile carriers having premium plans for higher spending consumers. Type of innovation notwithstanding, these sustaining innovations all give music rightsholders (bigger ones especially) a route to more revenue per user. This is optimisation. However, in a streaming value chain where a finite pot of money gets divided among constituents competing for share, optimisation can go both ways.

Take a look at things from Spotify’s perspective. Perennially under pressure from shareholders to improve margin, Spotify has neatly implemented four, margin improving, sustaining innovations:

Discovery mode which can give Spotify around 15% additional share (per Billboard)

Fraud fines issued to labels and distributors effectively means Spotify retains more revenue

Spotify’s “modernised” two-tier licensing means a big chunk of songs will not be paid royalties. If Spotify retains just a small portion of that, it is more margin. Even if Spotify gets to keep $0.00, two-tier licensing and anti-fraud measures will disincentivise the longtail, which will mean a slowdown in the number of low-revenue bearing tracks. This in turn will slow the rocketing of hosting fees, which means easing margin pressure

The infamous audio books bundle sees less share going to music rightsholders, which in turn could (depending on book rightsholder payments) also mean more share to Spotify (per Variety)

On top of all this, Spotify has two mid-to-long term accelerators:

1. Spotify is growing its userbase in Global South markets, meaning it does not face the same growth slowdown concerns as its Western rightsholder partners

Featured Report

Q3 2024 music metrics Maturation effect

This report presents MIDiA consumer data for key music consumer behaviours and company financials for Q3 2024.Consumer data covered includes, streaming app usage, music behaviour and streaming activities....

Find out more…2. By building creator networks in non-music formats, it has a path to higher margin content

Herein lies the problem with sustaining innovation: when it means optimising at the expense of other members of the value chain, one person’s optimisation can be another’s de-optimisation.

Appetite for disruption

Sustaining innovation is so appealing because it brings the promise of low-risk growth. However, little new is ever built without risk. Streaming was risky once, too. In fact, back in 2010 it seriously looked like Spotify might have to launch in the US without the major labels (per The Guardian).

There are many ways in which the streaming model can be seriously innovated but thus far, caution has held that back. China’s streaming services show just how radically the user experience can be changed, but rather than innovating upwards, Western DSPs have had to innovate sideways, into new audio formats (Amazon Music Unlimited’s Audible integration is the latest case in point).

Sometimes you need to disrupt yourself before someone else does. Facebook is the textbook example. In 2012 it was still the dominant global social network, but a small photo sharing app named Instagram was beginning to gain momentum. Facebook bought it for, what at the time looked like a staggering $1 billion (per The New York Times). Swiftly adding WhatsApp and Messenger, Facebook pivoted towards mobile photo and video sharing. Nowadays, this is what we understand social media to be. Back then it looked like a different planet compared to the desktop world Facebook occupied.When you do it right, turning disruptive innovation in on yourself pays dividends.

Party like it’s 1999 - a little warning from history

In the late 1990s the CD reigned supreme. Annual growth was not as stellar as it had been earlier in the decade, but it was still holding its own, mainly because the record labels had hit upon a new growth strategy: price increases. There was no clear new format. The CD was both today’s format and tomorrow’s. The outlook was steady with unremarkable growth underpinned by price increases. Sound familiar?

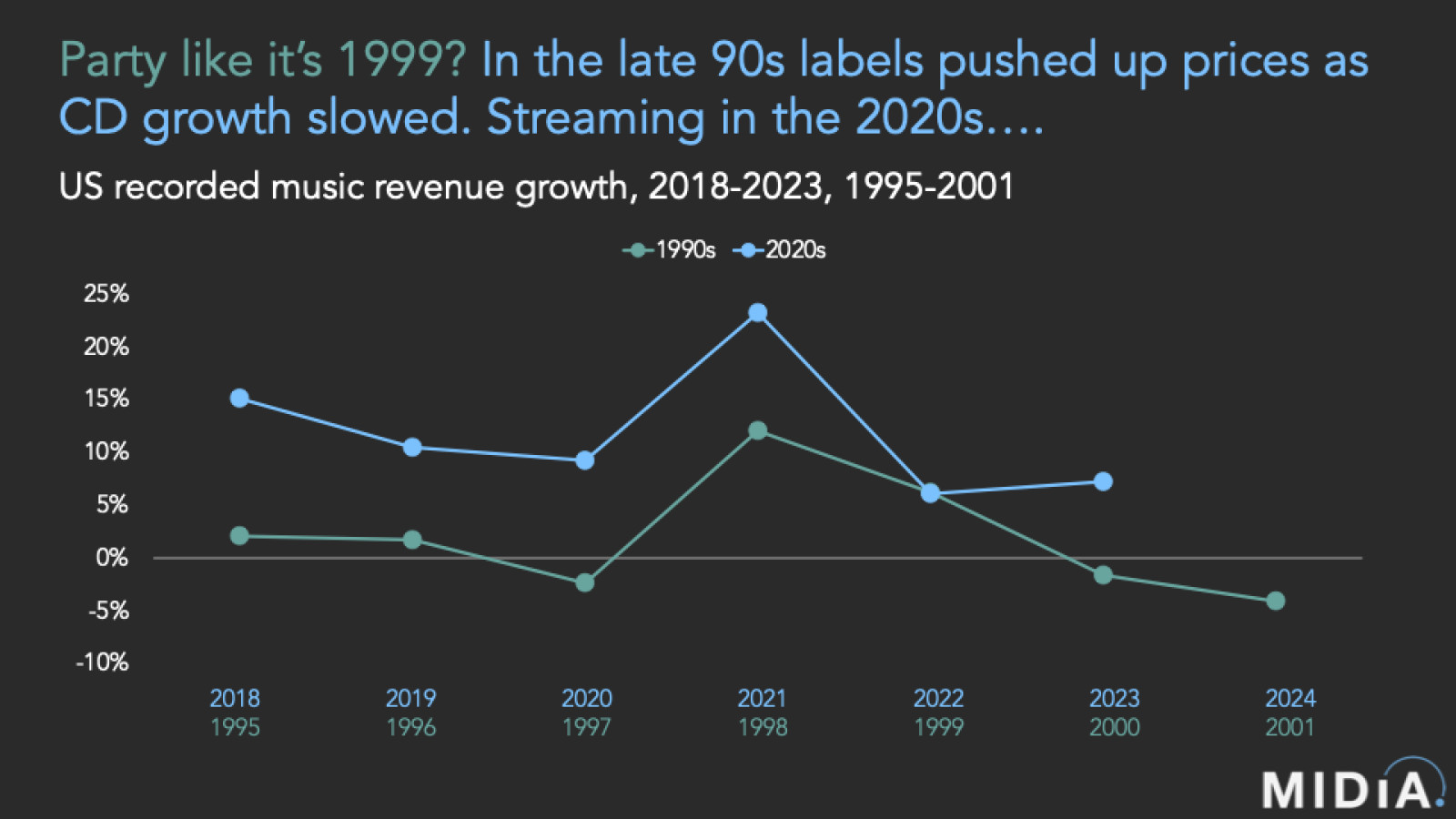

But that is not all, look at the spookily similar growth trends in the ‘growth through pricing’ phases of the CD and streaming:

To be clear, there is as much correlation as there is causality here. 2024 will almost certainly be a positive growth year, but the similarities are still important. In the late ‘90s, repeated price increases created the fertile breeding ground for peer-to-peer (P2P) piracy. It took a decade and a half for the music industry to really start to monetise the digital lane P2P had opened. Social music is at least somewhat monetised now, but still dramatically less so than streaming. The danger of optimisation pushing more consumers and creators to social is a real and present one. As MIDiA’s “Bifurcation theory” posits: social will not kill off streaming like P2P did the CD, instead it will coexist, but only as long as – you guessed it – streaming innovates.

Also, this time around, the labels are much better prepared for managing change. Label short-sightedness gave piracy a helping hand, as The Guardian’s Dorian Lynskey puts it: “‘90s executives were too busy worrying about the next quarter to consider the next decade”. Nowadays, labels spend a lot of time, resource and energy thinking about long-term strategy, as recently evidenced byUMG’s Capital Markets Day.

However, prepared or not, the streaming side of the music business needs to think hard about whether sustaining innovation is enough. To be blunt, if streaming doesn’t disrupt itself, social will.

The discussion around this post has not yet got started, be the first to add an opinion.