Songwriters Aren’t Getting Paid Enough and Here’s Why

Music Business Worldwide recently ran a story on how Apple has proposed a standard streaming rate for songwriters, with Google and Spotify apparently resistant. Of course, Apple can afford to run Apple Music at a loss and has a strategic imperative for making it more difficult for Spotify to be profitable, so do not assume that Apple’s intentions here are wholly altruistic. Nonetheless, it shines a light on what is becoming an open wound for streaming: songwriter discontent. In the earlier days of streaming artists were widely sceptical, but over the years have become much more positive towards the distributive medium. The same has not happened for songwriters for one fundamental reason: they still are not paid enough. This is not simply a case of making streaming services pay out more; rather, this is a complex problem with many moving parts.

Songwriters don’t sell t-shirts

Streaming fundamentally changes how creators earn royalties, shifting from larger, front-loaded payments to something more closely resembling an annuity. In theory, creators should earn just as much money, but over a longer period of time. If you are a larger rightsholder then this is often wholly manageable. If you are a smaller songwriter or artist, then the resulting cash flow shortage can hit hard. Many artists, especially newer ones, have made it work because a) streaming typically only represents a minority of their total income, and b) the increased exposure streaming brings usually boosts their other income streams such as live performances and merchandise. Professional songwriters however – i.e. those that are not also performers – do not sell t-shirts. Royalty income is pretty much it. There is a greater need to fix songwriter streaming income than there was for artists.

The four factors shaping songwriter income

Featured Report

Ad responsiveness in the era of content saturation

The digital entertainment space is more saturated than ever, with content spread and duplicated across dozens of platforms, from social to streaming. Advertising and marketing teams face incredible competition...

Find out more…There are four key factors impacting how much songwriters earn from streaming, and most of them can be fixed. To be clear, though, just fixing any single one of them will not move the dial in a meaningful-enough way:

- Streaming service royalties: Songwriter-related royalties are typically around 15% of streaming revenues, which represent around 21% of all royalties paid by streaming services – around 3.6 times less than master recordings-related royalties. This is better than it used to be, when the ratio was 4.8. However, there is clearly still a large gap between the two sets of rights. Labels argue that they are the ones who take the risk on artists, invest in them and market them. Therefore, they should have the lion’s share of income. Publishers, on the other hand, argue that they are increasingly taking risks with songwriters too (paying advances) and working hard to make their music a success, e.g. with sync streams. They also argue that everything is about the song itself. Both arguments have credence, but the fact that streaming services have historically negotiated with labels first helps explain why there isn’t much left of the royalty pot when they get to publishers. There is clearly scope for some increase for songwriters, but if there is not an accompanying reduction in label rates – not exactly a strong possibility – then the net result will be reduced margins for streaming services. Given that Spotify has only just started generating a net profit, the likely outcome would be to weaken Spotify’s position and skew the market towards those companies who do not need to see streaming pay – i.e. the tech majors. If the market becomes wholly dependent on companies that thrive on squeezing suppliers… well, good luck with that.

- CMOs: Many songwriter royalties are collected by collective management organizations (CMOs). These (normally) not-for-profit organisations administer rights, take their deductions and then either pay to songwriters directly or to publishers who then pay songwriters (after taking their own deductions). It gets more complicated than that, however. If a songwriter is played overseas, the local CMO collects, deducts and then sends the remainder to the CMO where the songwriter is based (however there are a good number of exceptions to this with a number of CMOs not deducting for overseas collections). That CMO takes its deduction and then distributes. It gets more complicated still – some CMOs apply an additional ‘cultural deduction’ on top of their main fee before distributing. So, if a US hip-hop artist gets played in Europe, the local CMO will take its cut, and an administration fee. Then it goes to his local CMO which takes its fee before sending it to the publisher which then takes its own cut (typically just 25%) which however is much better than label shares.

- The industrialisation of song writing: With more music being released than ever, songs have to immediately grab the listener. To help ensure every part of the song is a hook and to try to de-risk their artists, bigger labels commission songwriter teams and hold song writing camps, where many song writers get together and write the tracks for albums. This means that the royalties for every song are thus split into small shares across multiple songwriters. Drake’s ‘Nice for What’ has 20 songwriters credited. That means the already small royalties are split 20 ways.

- The unbundling of the album: When music was all about selling physical albums, songwriters used to get paid the same mechanical royalty for every song on the album, regardless of whether it was the hit single or filler. Now that listeners and playlists dissect albums, skipping filler for killer, a weak song simply pays less. Tough luck if you only wrote the filler songs on the album. On the one hand, this is free market competition. If you didn’t write a song well, then don’t expect it to pay well. Some songwriters argue that it should go the other way too, though – if they wrote the song that made the artist a hit, then shouldn’t they be paid a larger share?

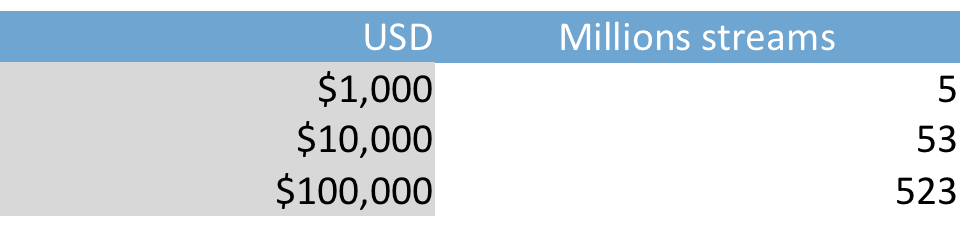

Here’s another way of looking at it. With the above analysis, this is how many streams the songwriter needs to earn income based assuming the songwriter is equally sharing income four ways with three additional songwriters:

It is incumbent on all of the stakeholders in the streaming music business to collectively work towards making earning truly meaningful income from streaming a realistic objective for songwriters. No single tactic will move the dial. Increasing the streaming service pay-out from 15% to 20%, for example, would still see the above-illustrated songwriter only earn 25% of that. All levers need pulling. Until they are, songwriters will feel short-changed and will remain the open wound that prevents streaming from fulfilling its creator potential. Ball in your court, music industry.

Note - since originally publishing this post I have had useful feedback from a number of rights associations and publishers. My assumptions actually translated (unintentionally) into a worst case scenario that was not representative of usual practise. The post has been updated to show a more typical revenue flow. The underlying arguments of the piece remain unchanged.

The discussion around this post has not yet got started, be the first to add an opinion.