What the 2018 Success of the Beatles for UMG Tells Us About Where Streaming is Heading

Universal Music Group recorded an impressive €6 billion in revenue in 2018, bolstering a JP Morgan valuation of $50 billion. No doubt, UMG is enjoying a purple patch, riding and driving the wave of recorded music industry growth. But as with an any industry transition, progress is not linear and the past can have a lingering embrace. In UMG’s earnings report lies a small but crucial detail that point to the fact that the music industry’s path ahead may not be quite as straight as it first appears: the continued success of the Beatles.

The Beatles were UMG’s fourth best seller in 2018

On page 13 of Vivendi’s year-end financial report, the Beatles’ ‘White Album’ is listed as UMG’s fourth best seller in 2018.It finished ahead of frontline artists including XXXTentacion, Migos and Ariane Grande. Above it were Drake’s ubiquitous ‘Scorpion’, Post Malone’s ‘Beerbongs & Bentleys’ and the soundtrack to ‘A Star is Born’. On the one hand this reflects the continued importance of the Beatles as a revenue driver for UMG. The Beatles, along with Abbey Road, were among the ‘crown jewels’ that UMG gained when it acquired EMI in 2012, so it is encouraging for UMG that the Beatles continue to deliver top tier revenue. However, Beatles revenue is not only a very different thing from Drake revenue, it also highlights the earnings divide between physical sales and streaming.

Streaming’s twin promise

The long-term promise of streaming is the combination of:

- Delivering larger audiences

- Replacing near-term, large volume revenue for a longer-term, annuity-like income model

Item number two happened very quickly; item number one is still in progress, but moving sufficiently enough to ensure many artists are now able to earn meaningful streaming income. However, we are not yet at our streaming destination, which is illustrated by the prominence of the Beatles in UMG’s 2018 sales. A ranking that owes little to streaming.

The Beatles are not a streaming powerhouse

According to the BPI, music from the 1960s accounted for just 3.6% of catalogue streams in the UK, which represents about 2% of all streams. Let’s assume the Beatles account for 40% of those streams – which is probably a generous assumption, this would mean the Beatles represented 0.8% of the $9.6 billion of streaming revenue in 2018, which translates as $79 million, which in turn equates to 2.7% of UMG’s 2018 streaming revenue. A meaningful amount for sure for a single artist, but not that significant in the greater streaming scheme of things. Therefore, the Beatles did not get to be UMG’s fourth biggest seller through streams. Instead, it did so through physical sales.

The main release in 2018 was the 50th Anniversary edition of the White Album. This premium physical release includes a $25 edition, right through to a $145 deluxe box set. With such high-unit prices, only small numbers need be sold to generate meaningful revenue.

The main release in 2018 was the 50th Anniversary edition of the White Album. This premium physical release includes a $25 edition, right through to a $145 deluxe box set. With such high-unit prices, only small numbers need be sold to generate meaningful revenue.

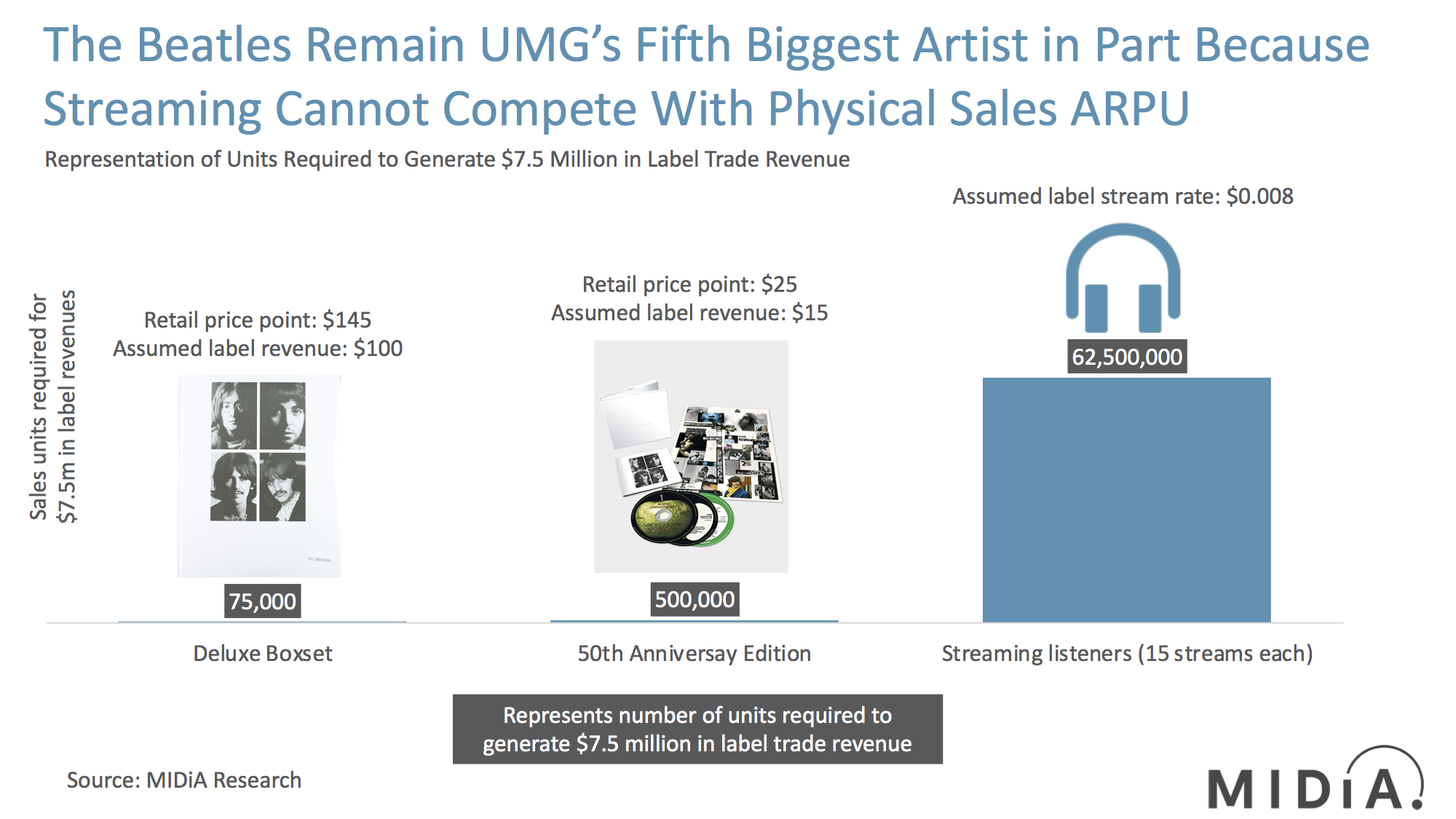

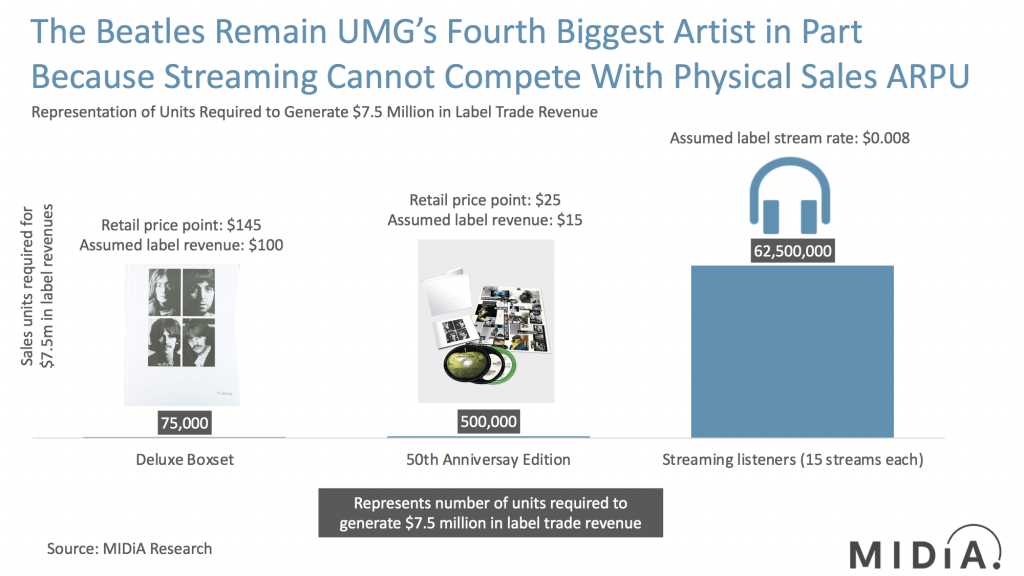

To illustrate the point, let’s assume UMG collects around $15 of the $25 retail price and $100 of the $145 edition. To generate $7.5 million of label revenue, UMG would need to sell just half a million copies of the $25 edition and only 75,000 of the Boxsets. To generate the same $7.5 million from streaming UMG would need to have 62.5 million people each streaming 15 tracks from the album. $7.5 million is incidentally also roughly the amount a label would earn from selling a million copies of a standard priced album.

Streaming cannot yet match CD-era album revenue metrics

This gets to the heart of the matter of why streaming is creating, alongside a welcome growing body of middle-tier artists, a small handful of megastars. To replicate physical sales success, an artist must have exceptional streaming success. To replicate standout physical success requires as yet ungraspable streaming success.

For example, the number one album in the US in 2000 – NYSNC’s ‘No Strings Attached’ - sold over nine million copies, which would require 600 million people each streaming it all once — roughly 8.5 billion streams — to generate the same income. That is more streams than the entirety of Drake’s 2018 Spotify streams across the entire planet – Drake was Spotify’s most streamed artist. In short, streaming is currently large enough to make record labels grow, but not yet vast enough to create artist-level revenue on the same scale that that the CD peak once did.

Longer-term revenue may, or may not, add up.

The counter argument is that over a number of years the revenue will add up to the equal. But even with that assumption, an album would need to generate around a billion streams a year over eight years to replicate the success of NSYNC’s ‘No Strings Attached’. No easy task when you factor in the dynamics of streaming consumption i.e. playlists replacing albums, new music being pushed over catalogue etc.

None of this is to suggest that streaming is failing, nor that UMG’s revenues are in question. Both are doing well. Instead, it is evidence that we still have much distance to go with streaming before we can start seeing artist-level successes on a par with the peak of the industry. Though of course streaming-level success needs measuring differently than CD-era success, so these comparisons provide context rather than performance targets.

Will there ever be another Beatles’ greatest hits?

One intriguing post-script to all of this is that with download revenue falling by 15% in 2018, and physical by 7%, the days of large-scale album sales are long gone. When this is considered alongside the Beatles’ under-representation on streaming, the elephant in the room is whether UMG would ever risk releasing a Beatles greatest hits album for fear of underwhelming sales numbers damaging the Fab Four’s legacy. The last greatest hits was ‘1’ back in 2000 during the EMI years. Might it just be that UMG bought the Beatles too late ever to release their last ever greatest hits?

There are comments on this post join the discussion.